Not even 48 hours in, and the Los Angeles 2024 bid already has it all over Boston after meetings Thursday in Switzerland with the International Olympic Committee. Compare and contrast: Earlier this year, the world alpine ski championships were staged in Vail, Colorado, the biggest Olympic sports event in the United States in years. The IOC president himself, Thomas Bach, showed up. Did the then-Boston 2024 bid chief, John Fish? No. When Steve Paglicua replaced Fish, he thereafter flew fairly quickly to Switzerland. Did he get a meeting with Bach? No. A photo op with the IOC president? Nope.

On Thursday, LA mayor Eric Garcetti and U.S. Olympic Committee board chairman Larry Probst met for about a half hour with the IOC president. Where? In Bach’s private office at IOC headquarters along Lake Geneva, a campus known as the Cheateu de Vidy.

After that, the mayor, Probst, USOC chief executive Scott Blackmun and LA24 bid chairman Casey Wasserman met for another half-hour with senior IOC officials: Olympic Games executive director Christophe Dubi; director general Christophe de Kepper; and the head of bid city relations, Jacqueline Barrett.

“Any campaign is about relationships,” Garcetti said in a teleconference with reporters following the Lausanne get-togethers, and perhaps in no sphere is that emphatically more true than in the Olympic bid game.

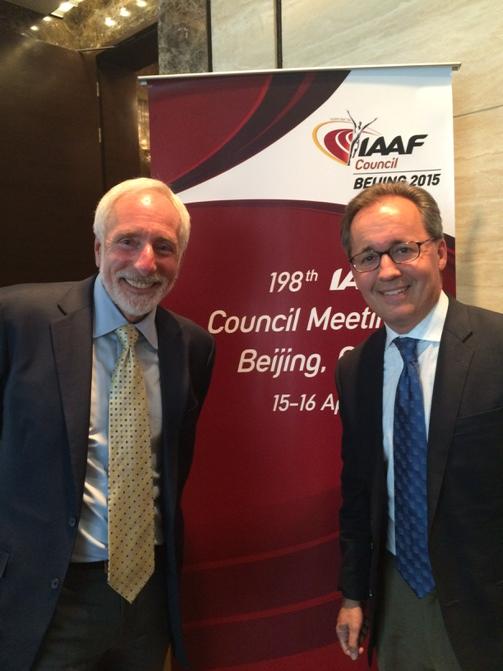

Photo op? Here you go.

There are hardly any guarantees in an Olympic bid race, this one starting formally on September 15, ending in the summer of 2017 with an IOC vote in Lima, Peru. That said, it’s clear, too, that the Olympic side not only wants but welcomes the LA effort.

After Boston withdrew in late July, Bach made it explicitly clear that the IOC expected a United States bid.

Blackmun said on that teleconference, referring to Boston, “Admittedly this was not a direct route we took to getting here,” meaning to LA24. At the same time, he stressed, “We could not be more pleased.”

“Boston made a decision that was probably right for Boston,” Garcetti said. “Los Angeles made a right decision for Los Angeles.”

Before its formal late July withdrawal, it had been clear for months within the Olympic world that Boston was a dead horse. It also had been plain that once Boston went away there would be one week of bad publicity, as the focus turned elsewhere, meaning LA. That is exactly what happened.

Asked if there were any concerns Thursday that LA might be considered a second choice, Garcetti said, “Quite the opposite,” adding, “They universally expressed excitement and enthusiasm about Los Angeles. It was not a backward-looking conversation at all.”

Which should be exactly the IOC’s response — because it offers the chance to prove that Agenda 2020, Bach’s would-be reform plan, is more than just words.

One of the changes Agenda 2020 has brought about is what’s called an “invitation phase” in the bid process; in practice, it affords a national Olympic committee the chance to explore one option and then, if it doesn’t play out, switch to a better one.

Also expected to be in the 2024 race, the first to fully test the Agenda 2020 reforms: Paris, Rome, Budapest and Hamburg, Germany. On Wednesday, the French Olympic Committee kick-started its messaging with a campaign called #JeReveDesJeux. That means, “I dream of the Games.” The plan in France is to sell wristbands with that slogan to help finance the Paris campaign.

In a fascinating turn, a look at the IOC’s consultants list, another new facet in the spirit of transparency owing to Agenda 2020, shows that Hamburg has already hired the services of seven — seven! — consultants. Paris: six, including UK-based Mike Lee, whose winning track record includes Rio 2016. Rome: four. The USOC has retained four, all well-known and -respected in the Olympic bid world: Americans Doug Arnot, George Hirthler and Terrence Burns, and UK-based Jon Tibbs.

Budapest: none.

As for what was actually said in Thursday’s meetings? Not much tremendously substantive, really.

Not that anyone should have expected anything fabulous, Probst saying on that teleconference that discussions were intentionally broad, “kept at a really high level.”

Does that matter?

No.

Once more, this was mostly — if not primarily — an exercise in relationship-building and in validation of process, in particular for the USOC and IOC.

In a statement, Probst said, “I would also like to thank the Olympic movement for its patience, as this has been a very important decision for the future of the movement in the United States. The LA 2024 bid enjoys the full support of the USOC -- our athletes, national, state and regional leaders -- and the Los Angeles city council and residents," with a poll showing 81 percent local support for the Games. "Our bid to bring the Games back to the U.S. for the first time in more than a quarter century begins right here, right now."

“This is a new LA,” Blackmun said on the teleconference, reflecting the enormous change in the city and in Southern California since 1984, and that surely and appropriately will be a key messaging point going forward.

The mayor said the idea was to start making the point that — again, completely consistent with one of the drivers of Agenda 2020 — that “we show that exciting Games and sustainability are not mutually exclusive.”

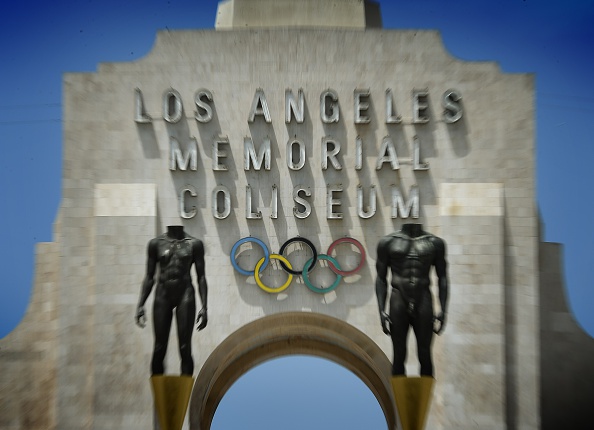

For his part, Bach said in a statement provided to Associated Press by the IOC, "Los Angeles is a very welcome addition to a strong field of competitors. We have been informed that LA 2024 has already embraced the Olympic Agenda 2020 reforms by making use of many existing facilities and the legacy of the Olympic Games 1984. Their vision is for the Olympic Games to serve as a catalyst in the development plan for the city."

As was pointed out Tuesday in the news conference on Santa Monica Beach where the mayor, Wasserman and others, including the 1980s and ‘90s swim star Janet Evans, helped launch LA24, 85 percent of the venues for the 2024 Games are already on the ground or are in planning regardless of an Olympics, 80 percent of them new since the 1984 Summer Games.

The operating budget stands at $4.1 billion; because of the way Olympic revenue streams work, including the IOC contribution, sponsorship and ticketing, an LA24 Games would very likely make a considerable surplus.

Also in the budgets, separately: $1.7 billion in non-operating costs — meaning construction, renovation and infrastructure such as planned Olympic Village. A huge chunk of that is expected to be paid for with private funds, including $925 million from a to-be-named developer on the village project.

“First and foremost,” Garcetti said, “my responsibility is to my city through its infrastructure and fiscal health. I would never do anything to endanger that.”

Garcetti, in that teleconference, also said that a central touchpoint Thursday was highlighting the notion that LA 24 is “a bid Los Angeles wants to do, the United States wants to do,” adding “clearly you can do that best in a face-to-face meeting.”

The point about this being not just an LA bid but an American one is — and will become even more so going forward — key.

On Wednesday, President Obama’s press secretary, Josh Earnest, told reporters aboard Air Force One en route to Dillingham, Alaska, that “obviously the president and the First Lady are very enthusiastic and strongly supportive of the bid put forward by the city of Los Angeles.”

In an Olympic bid context, it is always entirely and thoroughly appropriate for the head of government or state to offer such support.

But the comments also underscore a key U.S. challenge in the Olympic bid arena.

Again, relationships: since he took office in 2013, Bach has met with roughly 100 national leaders. Obama? No. And there is no indication a meeting is on either party’s agenda. Within the IOC, the president and First Lady are mostly remembered for the way they handled their trip to Copenhagen in support of Chicago’s 2016 campaign; Chicago got bounced in the first round.

Of course, a new U.S. president will have been in office for about eight months by the time the IOC votes in Lima in 2017.

In the more near-term: it matters for LA24, and significantly, that the U.S. government might actually step up big-time in connection with the Assn. of National Olympic Committee meetings to be held in Washington in October, and ensure that the delegates from more than 200 national Olympic committees — dozens will be IOC members — get through customs and border with not just ease but grace.

If you want to win the Olympic bid game, you have to understand the rules.

Like going to see the IOC president.

And the symbolism of the pictures — especially when you do, or don’t, get them.

Don’t be fooled, the pics can be tremendously telling. As the young people in their teens and 20s that the IOC is so keen to reach is always saying: "Pics, or it didn’t happen.”

As the mayor, Wasserman, Probst and Blackmun, head home, pics in hand, they know full well that two years is a long time.

But this, too: it has been a great two days for LA24. The launch probably could not have gone any better.

In a statement, Garcetti said, "It was an honor to meet with President Bach to discuss our initial bid. The Olympics are part of LA’s DNA – and we appreciate the opportunity to share our Olympic passion with the IOC and strengthen a movement that seeks to unite the world in friendship and peace through sport. After visiting the IOC headquarters, we are fully aware of, and ready for, the hard work ahead of us."

Just so, and to be clear, this caution: at the end of the day, this 2024 campaign will end up being about whether the IOC members want the Games back in the United States, or not.

In this dynamic, LA is not just LA. It’s way more. It’s LA representing the United States of America.

“I think it is time for America to bring the Olympics back home,” Garcetti said, adding, “The United States loves the Olympics, and the Olympics loves the United States.”

Now we will get to see — with a world-class bid that is, in theory, everything the IOC could want to fulfill Agenda 2020 — if that is, indeed, true.