LAUSANNE, Switzerland — To use a favorite saying of Thomas Bach's, the International Olympic Committee president, the IOC’s policy-making executive board and Bach himself did a great job -- over three days of meetings that wrapped up Thursday -- of talking the talk.

Amid corruption and doping scandals in, respectively, soccer and track and field, the IOC board and president talked up the import of maintaining — if not restoring — the credibility of international sport.

There was celebration of the one-year anniversary of the ratification of Bach’s would-be reform plan, the 40-point Agenda 2020. The executive board heard at length from one of the world's prominent business professors, Didier Cossin, based at the Swiss institution IMD; he talked for nearly two hours about best practices and good governance. Bach himself wrote a newspaper-style op-ed that, without once mentioning the soccer and track governing bodies FIFA and the IAAF, described campaigns against the three primary challenges confronting world sport: betting and match fixing, doping and, finally, bribery and other corruption.

All this is, to be sure, excellent talk.

But it totally, completely and fundamentally misses the point about why the IOC is being lumped in — right or wrong, fair or not — with FIFA and the IAAF in the minds of many around our globe, and why world sport, and in particular the Olympic movement, is facing a perhaps unexpected but potentially unprecedented challenge.

For 57 years, British writer David Miller has been covering the Olympic movement. Just before Thursday's wrap-up news conference, the IOC handed out a release that in print ran to three pages; it broke little new ground, if any, amid a lengthy recitation of governance and doping matters. Miller: "It's like a notice from the water board about drainage."

To be blunt: where is the joy?

Increasingly, voters and taxpayers in western democracies have turned against the IOC. Alone in the world of sport, it boasts as its raison d'être a message of tolerance, pluralism and more. But the IOC is failing, time and again, at conveying the inspiration and joy inherent in and provoked by seeing humankind, together, gathered in a real-time reminder of what can connect — not divide — us.

The latest: Hamburg’s bid for the 2024 Summer Games shot down on the last Sunday in November in a referendum.

This comes after the turbulent 2022 Winter Games campaign, which saw Beijing elected over Almaty, Kazakhstan, the only two survivors, after six European entries pulled out: Oslo; Stockholm; Davos/St. Moritz; Krakow; Munich; Lviv.

Beijing! Where the authorities this week had to issue a red-alert smog warning, photos showing the famed Bird’s Nest barely visible in the grey air. This after assurances that the 2008 Summer Games were going to make major headway in solving China’s pollution problem.

Four cities remain in the 2024 hunt: Los Angeles, Rome, Budapest and Paris, in the order in which they will present going forward, according to lots drawn Wednesday at the lakefront Chateau de Vidy, the IOC headquarters.

That is, assuming all four make it to the IOC vote in the summer of 2017. There are no guarantees.

The problem, to be clear, is fear of Games costs and wariness — if not more — with the IOC, and the perception, again right or wrong, fair or not, of the IOC members as elitists and the IOC itself at the head of a system that seems rife with misconduct.

The prompt may be the $51-billion figure associated with the 2014 Sochi Games. It might be the revelations of a culture of deep-seated corruption within FIFA. It is perhaps the spotlight on state-sponsored doping in Russia, with the seeming promise of yet more inquiry into the term of the immediate IAAF past president, Lamine Diack of Senegal, due to be made public in just weeks.

It’s time now for the IOC, again referring to Bach’s dictum, to walk the walk.

It needs not only to recognize but to act upon this fundamental truth:

The conversation needs to move away from money.

It’s that simple and, at the same time, that complex.

The IOC is in business, sure. But it is not, repeat not, fundamentally a business. It is not pushing baby food, chocolate and more like Nestlé; headquartered just down Lake Geneva in Vevey, Switzerland. It is not a bank like UBS, based in Zurich and Basel.

Instead, the IOC is in the business of promoting a set of values — friendship, respect, excellence, all of which add up to hope and dreams — and a universal ideal, the notion of a better world through sport.

What is missing right now, and has been, as evidenced by the 2022 pull-outs and the 2024 Hamburg defeat amid the promotion and implementation of the Agenda 2020 plan, is any real and sustained focus from the IOC in its communication on the basics:

Friendship. Excellence. Respect. Hope and dreams.

For any who might doubt, Bach is super-smart and -sophisticated. He is good at both broad scope and detail. He is an accomplished public speaker, and in English, a second language.

In his op-ed, he closed this way:

“As Nelson Mandela said: ‘Sport has the power to change the world.’ Yes, these are difficult times for sport. But yes, it is also an opportunity to renew the trust in this power of sport to change the world for the better.”

How? Not once in his opinion piece did the words “values” come up. Nor, in that context, supposedly at the heart of everything the IOC does, did “respect,” “friendship,” “excellence,” “hope” or “dreams.”

Thursday's three-page news release? Same. Not a mention in the relevant context.

You wonder why there’s a disconnect?

As the longtime Olympic bid strategist Terrence Burns outlined in a post Wednesday to his blog:

“Not enough people in Hamburg were sufficiently inspired by the Olympic brand.”

He continued:

“To me, the Olympic brand is and has always been about hope. The stated vision of the Olympic movement is ‘building a better world through sport.’ I’ll buy that. But what is the emotional payoff? What is the IOC’s singularly unique promise that no other brand can deliver?

“Again, I think it is hope. Hope inspires human beings to dream with no limitations.

“Hope is the emotional output of the Olympic brand. The Games, and more importantly the athletes, give us hope that something better resides deep inside of us and, if only for 17 days every four years, we are capable of undeniable grace. Nothing other than perhaps theology offers humankind a similar promise through the demonstration of human achievement.

“I am under no illusion that the IOC will suddenly revisit its core values in favor of the word ‘hope.’ What I am suggesting is that by ignoring the concept of hope, we are missing something powerful that is needed right now.”

To be clear, the IOC also cannot and should not adopt the position that it is above the discussion of the funds needed to stage a 21st-century Olympics.

It can and should do a better job of explaining the basic difference between an operating budget on the one hand and, on the other, whatever costs are associated with construction or infrastructure. The latter traditionally is the source of significant cost overrun.

That explanation is simply not that difficult.

According to figures made public Wednesday, the Tokyo 2020 plan is now credited with $2.9 billion in venue-related cost savings, purportedly due to Agenda 2020. It's worth asking: why were the members were so gung-ho for Tokyo in the first instance when, by contrast, rival Madrid’s entire capital budget for 2020 totaled $1.9 billion?

The Rio 2016 budget is now under intense pressure, organizers looking to cut some $530 million from the operating budget of roughly $1.9 billion, about 30 percent. Brazil is confronting a slew of challenges: financial (the country is in its worst recession in 80 years), political (president Dilma Rousseff is facing impeachment proceedings) and more (a kickback scandal centered on the energy giant Petrobas).

Bach said Thursday, referring to Rio 2016, "We are sure history will talk ... like history talks about Barcelona '92 in this respect," one of the greatest of Summer Games. At the same time, he said about Rio, "We know the situation there is not easy."

To paraphrase David Byrne and the Talking Heads: how did we get here?

This question is hardly unreasonable.

Nor -- let's be clear -- is any financially related inquiry in and around the Games.

The problem, big picture, is that the money discussion has all but hijacked any other discussion — in particular, the good the movement can and does do and the benefits that can come with staging an edition of the Olympics.

When Boston went out earlier this year, it was all because, purportedly, the mayor didn’t want to sign the host city contract, citing the worry of cost overruns. This after a vocal “no” campaign from locals worried about, again, the risk and reward of the “value proposition” that might or might not have been a Boston 2024 Games.

Los Angeles has since replaced Boston as the U.S. Olympic Committee’s candidate; in Southern California, the locals remember the glow of the 1984 Games, and polling indicates huge support for 2024.

For emphasis: this is by no means a USOC, or an American, problem.

It’s way bigger than that.

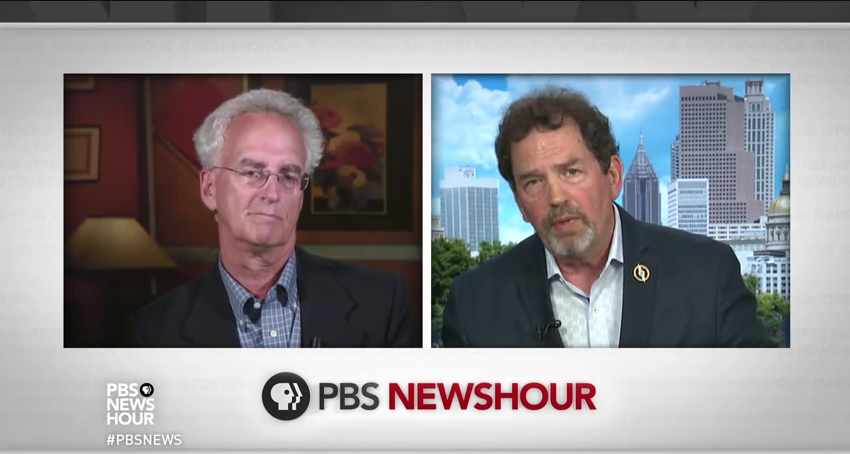

After Boston went out, the American television show NewsHour on PBS, the public television channel, hosted a debate between vocal Games critic Andrew Zimbalist and George Hirthler. Zimbalist is a Smith College professor. Hirthler is a longtime Olympic bid strategist, an unapologetic idealist for the movement and the author of a forthcoming novel on the life and times of the French Baron Pierre de Coubertin, widely acknowledged as the founder of the modern movement.

Hirthler:

“There’s a better story, and it’s the story of the Olympic movement and its value to our world. You never hear about it in the economic financial risk stories of the opponents of the Games.

“Right now the Olympic movement is at work in 200 countries around the world, 365 days a year instilling the values of excellence, friendship and respect — respect for opponents, other cultures, differences — in young children, millions of young children around the world. In our world, we need a positive force like that at work around the world.

“They invest — the Olympic movement invests $1-billion every year in the development of sport around the world. That money flows directly from the sponsorships and broadcast rights that are sold for the cities that are hosting the games. So the IOC draws money from these host cities in order to develop sport globally. I’d like to know what the value of the development of sport, giving kids a chance to choose sport everywhere — what’s the value of that economic development?”

Zimbalist, in response:

“Look, the Olympic movement is a good thing. Olympic values is a good thing. Nobody is contesting that.

“The issue that we were talking about is whether it makes economic sense for cities to host the Olympic Games, whether it pays off for them to do that.”

How hard would it be for the IOC to gin up a road show featuring the president, Games executive director Christophe Dubi, some IOC members (to show doubters that, indeed, they can be supremely normal) and, most important, key athletes?

Who wouldn’t want to be listened to and feel inspired by the likes of — just riffing here — Usain Bolt, Michael Phelps, whoever in whatever country?

Is there anyone who doesn’t like a Bud Greenspan movie? Bring the popcorn and the tissues.

In an email exchange this week, Hirthler said, “You can't win the economic argument because the opposition isn't rational -- you have to make the argument about why our world needs the Olympic movement -- why the Games hold more hope and promise for humanity than any other international institution.

“And that has everything to do with the grass-roots work of the IOC and global sport, which is the foundation of Coubertin's vision of uniting all humanity in friendship and peace through sport.”