EUGENE — Justin Gatlin cruised Sunday to victory in the men’s 100-meter dash at the 2016 U.S. Olympic Trials, setting in motion the next chapter in a long-running drama about the interplay of reality and perception mixed with the unlimited possibilities and enormous potential of redemption.

Or, not.

Gatlin, who is 34, ancient by sprint standards, ran 9.8 seconds to defeat Trayvon Bromell, who turns 21 next week, and Marvin Bracy, who is 22 and a former Florida State wide receiver who three years ago gave up football to run track. Bromell is the 2015 world bronze medalist; Bracy is the 2014 world indoor silver medalist at 60 meters.

Bromell ran 9.84, Bracy 9.98. The outcome was never seriously in doubt. Gatlin got off to his usual solid start and ran clean and hard through the line.

“I have new peers,” Gatlin said. “I have to be able to evolve with that. These young talented guys keep pushing me and I keep pushing them.”

The 100-meter final highlighted a series of finals under brilliant blue skies and before a solid crowd of 22,424 at historic Hayward Field.

In the women’s 400, Allyson Felix, running on a bum ankle, blew by the other seven women in the homestretch like they were standing still to win in 49.68. Phyllis Francis went 49.94, Natasha Hastings 50.17.

The call on NBC — “Here comes Allyson Felix! Felix just goes right by them!” — hardly does justice to her finishing kick. It was just — outrageous. As she crossed the line, she said, “Thank you, lord.”

“That’s why she’s great,” the NBC analyst Ato Boldon said. “Because somehow she always finds a way.”

“It’s up there,” Felix said afterward when asked to rate how the race ranks in her career. “I don’t think I’ve ever gone into a race with so much against me.”

Felix’s quest to qualify in the 200 as well gets underway with prelims Friday: “My goals haven’t changed at all.”

In the decathlon, Ashton Eaton earned the chance to go for back-to-back Olympic gold. Never really threatened, he took first with 8750 points. With Trey Hardee out because of injury, Jeremy Taiwo took second, with 8425. Zach Ziemek got third, 8413.

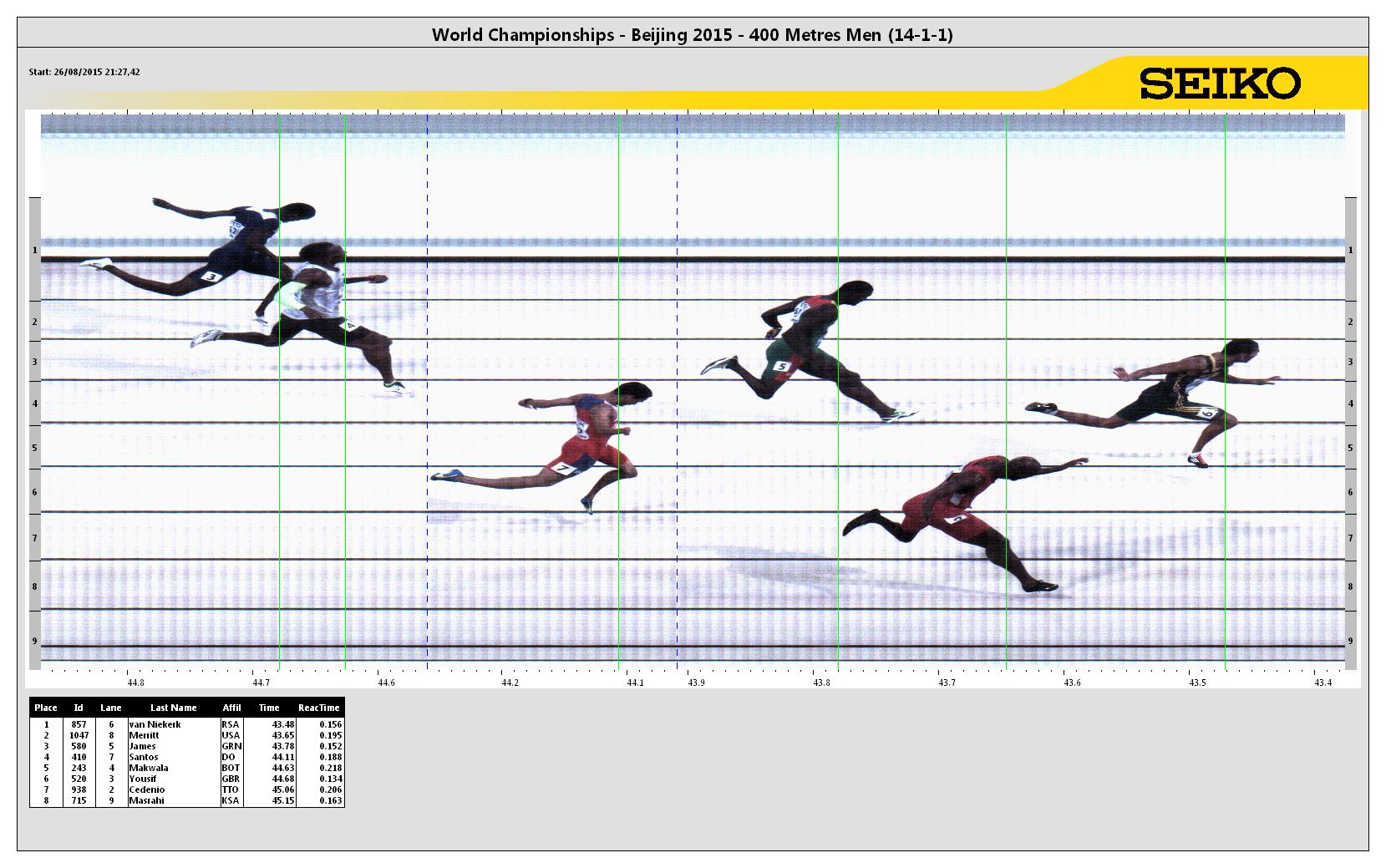

The men’s 400 saw LaShawn Merritt go 43.97, the eighth time he has broken 44 and, as well, fastest time in the world this year. Gil Roberts took second in 44.73, David Verburg third in 44.82.

In Rio, Merritt, the Beijing 2008 gold medalist in the 400, likely will resume his rivalry with Kirani James of Grenada, the London 2012 winner. “I trained very hard for this season,” Merritt said. “I wanted to go out there and win another Olympic Trials.”

The 32-year-old mother of three, Chaunte Lowe, won the women’s high jump, at 2.01 meters, or 6 feet, 7 inches — Rio will be her fourth Olympics. The 18-year-old Vashti Cunningham, the 2016 world indoor champion, took second, at 1.97, 6-5 1/2; she becomes the youngest U.S. track and field Olympian in 36 years. Inika McPherson got third, 1.93, 6-4.

“The high jump has never had this much depth,” Lowe said. “I had to train my butt off every day.”

In the men’s long jump, Jeffrey Henderson ripped off a fourth-round jump of 8.59, 28-2 1/4, for the win. In the next round, Jarrion Lawson went 8.58, 28-1 3/4.

Will Claye, the London 2012 long jump bronze medalist (and triple jump silver medalist), took third, with a fifth-round 8.42, 27-7 1/2. The Buffalo Bills wide receiver Marquise Goodwin finished seventh.

Marquis Dendy matched Claye’s jump but Claye held the second-longest jump tiebreaker. Dendy, meanwhile, pulled up limping after Round 4 and passed on his last two jumps.

Even so, and this makes for emphatic evidence of why the rules of track and field can be so trying for the average fan -- while Claye is the third-place finisher, Dendy is the third Rio qualifier.

USA Track & Field explains:

"Will Claye and Marquis Dendy each had marks of 8.42m/27-7.5 today with Claye holding the better secondary mark to secure third place. However, Claye’s best jump today was wind-aided and his best legal mark since May 1 of last year was an 8.14m/26-8.50 from the Trials qualifying round on Saturday, which is one centimeter away from the Olympic standard. There is no standard chasing at the track & field trials, thus Dendy is the third qualifier for Rio."

Moving along:

In a women’s 100 final that saw five of the eight go under 11 seconds, English Gardner ran to victory in 10.74. Tianna Bartoletta and Tori Bowie crossed in 10.78. Bartoletta on Saturday had qualified for the Rio women’s long jump, taking second behind Brittney Reese.

“Honestly, I remember 2012,” Gardner said, recalling her seventh-place finish here at Hayward four years ago, when she ran 11.28. “I sat in the car. And I cried my eyes out. I came to the realization I never wanted to feel that feeling again.”

“I have to conquer myself,” Bartoletta said. “One of the things I studied between jumps and between rounds is that conquering myself is the only victory that matters.”

She also said, “It really comes down to mental preparation or execution. Physics does not care how you feel or if you’re having a bad day emotionally. All you have to do is execute.”

Gardner added with a smile, “Our relay is going to be nasty,” and in this context “nasty” means good.

Justin Gatlin can far too often be portrayed in the worldwide press as nasty, and in this instance nasty means nasty.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. At the celebratory news conference, he brought his son, Jace, who just turned 6. The proud father said, “I’m glad my son is here.”

The victory in Sunday’s 100 sends Gatlin to his third Olympic Games and, presumably, his fourth major championship run against Jamaica’s Usain Bolt.

In the semis, Gatlin ran 9.83, the fastest time in the world this year. In the next heat, Bromell answered with a 9.86.

In the final about 90 minutes later, Gatlin, in Lane 3, was fully in control. He knew when he had crossed that he had won, flashing a left-handed No. 1 to the crowd.

Tyson Gay took fifth, in 10.03.

Lawson, having just taken second in the long jump, lined it up just a few minutes later in Lane 1 of the 100 final. He got seventh, 10.07.

When he was 22, Gatlin won the 2004 Athens Olympic 100.

By then, he had served a year off after taking Adderall. He took it to help stay focused for midterms at Tennessee. A stipulated agreement — between Gatlin and the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency — declared that Gatlin “neither cheated nor intended to cheat.”

In 2006, Gatlin — training with Trevor Graham, who would emerge as one of the central figures in the BALCO scandal — tested positive for testosterone.

To make a very long story as simple as possible, Gatlin would serve four years off for this second strike — even though he and supporters have long insisted, with sound reasoning, that the Adderall matter ought not to be held against him in a significant way, and even though it has long remained unclear how Gatlin came to test positive in 2006 for testosterone.

Jeff Novitzky, the federal agent who helped break the BALCO matter, would later testify that he had asked Gatlin if he “used any prohibited substances.” The answer: “His answer was no, never knowingly.” Novitzky added: “… I have not obtained any evidence of his knowing receipt and use of banned substances.”

It was during Gatln’s four years off that Bolt not only burst onto the scene but became the international face of track and field.

Not counting the 200 or relays:

Bolt is the Beijing 2008 and London 2012 100 champion. He also won the 100 at the world championships in 2009 (Berlin), 2013 (Moscow) and 2015 (back in Beijing).

Over the years, Bolt seemingly could do no wrong. Gatlin, meantime, was often painted — inappropriately — as a two-time loser instead of what he more accurately is: a victim of circumstances.

Bolt and Gatlin squared off In those Olympic and worlds 100s in 2012, 2013 and 2015.

In 2012, Gatlin got bronze.

In 2013, silver.

Last summer in Beijing, Gatlin had the race — but then couldn’t hold his form powering toward the finish line, stumbling just enough to allow Bolt to get by. Bolt finished in 9.79, Gatlin in 9.80.

For years, the British press in particular has savaged Gatlin.

“He’s saved his title, he’s saved his reputation — he may even have saved his sport,” the BBC commentator and former world champion Steve Cram exulted as Bolt crossed ahead of Gatlin in the 100. Many in the British press had painted the race as nothing less than a clash of good and evil.

At the Jamaican Trials, which went down over the past several days, Bolt pulled out with what has been described as a “Grade 1” hamstring tear.

It’s not exactly that his participation in Rio is in doubt. Pretty much everyone in track and field expects Bolt to be there.

The issue is what kind of shape Bolt will be in. Gatlin, here, said he ran through the same injury at the 2013 worlds — managing, he said, to be at maybe 75 percent.

https://twitter.com/usainbolt/status/749076079462277121

“He’ll be very fit to be in Rio,” assuming Jamaican officials select him, Ricky Simms, Bolt’s agent who is in Eugene, said Sunday.

Of course he will be selected.

If Bolt is healthy — enough — to make the Rio final, what if Gatlin — finally — prevails?

Is the world ready to accept Justin Gatlin as he is?

As an intelligent, eloquent guy with deep family ties? Who happily signs autographs and poses for pictures and selfies with kids and grown-ups alike?

As a man who has made mistakes — who hasn’t — but has fought, and hard, to come back.

As a man who not only loves competing for the American team but cherishes the opportunity to do so?

In answering those questions, compare and contrast the case of the whistleblower Yulia Stepanova.

The sport’s international governing body, the International Assn. of Athletics Federations, has banned Russia’s track and field team amid explosive allegations of state-sponsored doping.

The 800-meter runner Stepanova and her husband, Vitaly Stepanov, a former Russian anti-doping agency doping control officer, served as the two primary whistleblowers in a German television documentary that in December 2014 brought the matter to worldwide attention.

A few days ago, the IAAF gave Stepanova permission to compete in Rio as a “neutral” athlete.

Rune Andersen, who leads the IAAF task force investigating the Russian matter, in recommending Stepanova’s case be “considered favorably,” had also said, “Any individual athlete who has made an extraordinary contribution to the fight against doping in sport should also be able to apply.”

The matter is far from settled. At any rate, Stepanova might return to international competition as soon as this week’s European championships. She and her husband, and their young son, are now living in exile in the United States.

Consider, meantime, the way the Guardian — which among the British papers has actually been relatively restrained in its descriptions of Gatlin — described the latest IAAF turn in the Stepanova case.

The first paragraph said she “bravely and spectacularly blew the whistle on widespread doping inside her country.”

But wait.

She “bravely and spectacularly” went to the press only after she got tagged with a two-year doping suspension, and then, again to simplify a complex story, after being referred by a World Anti-Doping Agency official.

A report due out in a couple weeks is likely to provide even more damning evidence against the Russian sport structure.

Even so, the Stepanov allegations have yet to be tested in the crucible of any formal inquiry, and in particular on cross-examination. They are living in the United States — who is paying the family’s bills, and why? Vitaly Stepanov sent more than 200 emails to WADA — who sends 200 emails about anything? Wouldn’t a good lawyer love to ask if 200 emails sounds like someone with maybe issues?

Gatlin’s matters, meanwhile, have been thoroughly tested, and under oath.

In 2013, after she found out she had tested positive, Yulia Stepanova stated making secret recordings of her meetings with sports officials. In exactly the same way, as soon as he found out he tested positive in 2006, Gatlin went to the authorities and volunteered to try to get evidence against Graham. To be clear: he cooperated with Novitzky and the feds, in all making some dozen undercover phone calls

It would stand to reason that Gatlin got a break, right?

No.

The majority of the three-person arbitration panel hearing Gatlin’s case took note of the “extensive, voluntary and unique nature” of his assistance.

But the rule then at issue: it had to be “substantial assistance” that led directly to an anti-doping agency discovering or establishing doping by another person.

So — because Graham didn’t cop to anything on the phone with Gatlin, Gatlin got no break.

Compare — because the Stepanovs went to WADA and then got passed on to the press, she gets a break?

Moreover — Gatlin’s current coach, Dennis Mitchell, testified for federal prosecutors against Graham.

Still Gatlin — and, by extension, Mitchell — get no break in the court of public opinion, and Yulia Stepanova is brave and spectacular?

Where are the calls to ban Stepanova for life — like so many would-be moralists have done with Gatlin?

This is all a logical disconnect.

Because if Yulia Stepanova is brave and spectacular, isn’t Justin Gatlin, too?

“Just seeing what he has done over the years, and what kind of person he is,” Bromell said Sunday, referring to Gatlin, “that’s why I would like to have someone like him as a mentor. A lot of people don’t know how good of a man this guy is.”

He said a moment later, “The man is just good.”