Quick. Name the best wrestler on the Olympic and international scene the United States has ever produced. The name most people would name -- if, that is, they could name even one name -- would be Dan Gable, who won Olympic gold in Munich in 1972 while not giving up even a single point. The Gable legend was, over the years, further enhanced by his incredible coaching career at the University of Iowa.

There are, of course, others. Just to name a few, and the proud history of American wrestling means a list like this runs the risk of omitting many others: Lee Kemp, Dave Schultz, Steve Fraser, Bruce Baumgartner, John Smith, Cael Sanderson, Rulon Gardner, Henry Cejudo.

A few days ago, 25-year-old Jordan Burroughs won the 74-kilo/163-pound freestyle class at wrestling's world championships in Budapest, Hungary. The victory ran Burroughs' unbeaten streak to 65. The man has not lost at the senior level since he started competing internationally.

The sport of wrestling, as is widely known, got itself back into the Summer Games in 2020 and 2024 via a vote earlier this month by the International Olympic Committee's full membership in Buenos Aires. That's a big win. But, to be blunt, there's still has a long way to go. Wrestling, to sum up, has a Jordan Burroughs problem.

It's not that Jordan Burroughs himself is a problem.

Far from it.

The problem is the other way around. Who knows about Jordan Burroughs?

Now that wrestling is back in, the same energy, enthusiasm and passion that got it there has to go toward building the brand. Right now, wrestling has a window of opportunity. Burroughs is without doubt its biggest current star, particularly in the United States.

So why isn't he on SportsCenter? Leno? Letterman? Conan? The Daily Show? The Colbert Report? Making the rounds of the early-morning TV shows as well? Being offered up for bit roles in movies? For that matter, why aren't people scrambling to make documentaries about him -- or making him the centerpiece of films such as The Great Wrestling Comeback of 2013?

Wrestling is huge in Russia. Wouldn't it score political points to bring Burroughs to Sochi to have him mingle with the IOC bigwigs and maybe even Russian President Vladimir Putin himself this coming February?

Attention, Billy Baldwin. You were front and center in the months up to the IOC vote. By all accounts, you played a significant role in rallying Hollywood and even Wall Street in fund-raising drives that helped lift wrestling's profile.

Now comes Phase Two.

"The Miami Heat," Burroughs said in a phone interview, "had a 27-game winning streak. It was all on SportsCenter. It got huge press. Here I am at 65 and no one even knows.

"This is important to help the sport," he emphasized. "It is not important to me personally. It is something I wish we could do more of. It is not, let me repeat, something to me to be a self-fulfilling guy."

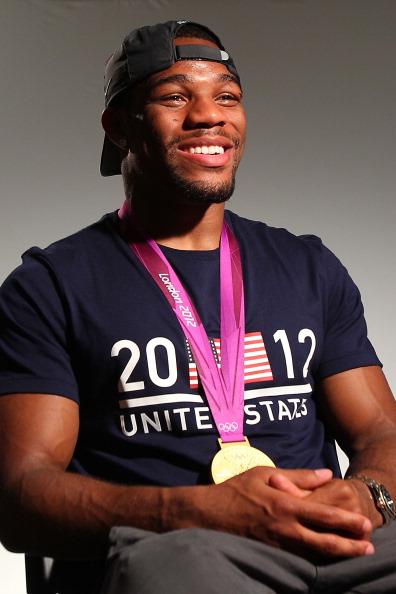

Burroughs is the 2012 Olympic gold medalist; the 2011 world champ; and, now, the 2013 world champion, too. He is a two-time NCAA champion, in 2009 at 157 pounds and in 2011 at 165. In 2011, he won the Hodge Trophy, wrestling's equivalent of football's Heisman.

In the final in Budapest, Burroughs defeated Iran's Ezzatollah Akbarizarinkolaei, 4-0. The victory made him the first U.S. men's freestyle wrestler to win back-to-back world titles since Smith, in 1990 and 1991. Burroughs also became only the second U.S. men's freestyle wrestler to win three straight world or Olympic titles; Smith won six straight world or Olympic titles from 1987-92.

The victory in Budapest is all the more remarkable because, as Burroughs disclosed afterward, he suffered a broken ankle training Aug. 22 in Colorado Springs, Colo.; he had surgery the next day and at the worlds still had five screws in his left ankle for stability. He guessed he was perhaps at 75 to 80 percent when he arrived in Hungary.

Burroughs is thoughtful, well-spoken, an incredible role model. He is just about to get married. He is everything USA Wrestling -- indeed, the U.S. Olympic Committee -- would want.

Even so, Jordan Burroughs could walk down most streets in the United States of America and no one would know who he is.

On most blocks they know who LeBron James is. And Peyton Manning. Switching to Olympic sports -- Michael Phelps and Apolo Ohno, too.

But not Burroughs.

That is a big problem for a sport that is -- and make no mistake about it -- still going to be fighting for its Olympic life.

As Serbia's Nenad Lalovic, the new president of FILA, the sport's international governing body, said in an interview in Buenos Aires, a couple days after the IOC vote, "This job is not finished. We are just starting."

Burroughs is a bigger star in Iran than he is in either New Jersey, where he grew up, or even Nebraska, where he went to college. This fall, Taylor Martinez, the Cornhuskers' starting quarterback, is a way bigger deal in Lincoln.

In Teheran? This past February, the U.S. team took part in a World Cup there. The just-released book "Saving Wrestling," by James V. Moffatt and Craig Sesker, is filled with inside nuggets on wrestling's path back to 2020. As the book recounts, in Teheran, after he won, Burroughs had to be pushed through the crowd by U.S. assistant coach Bill Zadick to get to the team bus.

Mind you, this was a crowd of bearded Iranian men seeking photos or an autograph from an American wrestler. The two countries' political leaders -- until President Obama's telephone call last week to Iranian President Hassan Rouhani -- have had no high-level contact since 1979.

Burroughs says in the book, "I received more attention there than I receive on my home soil. It was kind of like being Justin Bieber with all the attention that I was getting. It was nuts."

The competition in Iran took place just days after the IOC's policy-making executive board move to boot wrestling out of the Games.

As the saying goes, sometimes a crisis presents unexpected opportunity.

In wrestling's sake, the sport effected in seven months the sorts of changes -- political, governance, rules -- that would otherwise have taken 15 or 20 years. Or maybe longer.

"This is the best thing that ever happened to wrestling," said Jim Scherr, the former USOC chief executive who played a key role in presenting FILA's winning case to the IOC.

Among the changes were the development of women's and athletes' commissions. FILA didn't have such boards. So simple. One of the members of the new athletes' commission is American Jake Herbert, a 2012 Olympian. He called it a "step in the right direction," adding, "They are getting there."

This is the thing, though -- they are not there yet.

The sport essentially faces two big-picture challenges, all of which is clear from reading the IOC materials that led to the executive board action in the first instance:

One, it needs to do a much better job of promoting itself at the high end, meaning the creation and promotion of a brand and image for the sport and its athletes.

Two, at the grass-roots and club levels it needs to attract way more kids and young people -- boys and, in particular, girls -- and make the sport more friendly to them and their parents.

Bill Scherr is Jim's twin brother. Bill is chairman of what was called the Committee for the Preservation of Olympic Wrestling, and said, "All sports federations have their problems and issues. 2024 is 11 years away." Referring to FILA, he added immediately, "We face elimination again. I would think they would be motivated to make the changes necessary."

This all leads back to Jordan Burroughs.

It's not complicated. All sports thrive on stars.

When he gets back from his honeymoon, you'd like to think there would be some really smart people waiting to talk to him. With real money for a PR campaign, or two, for the sport, built around this All-American guy.

"What wrestling has done," Burroughs said, "is put itself back in the spotlight." In Rio de Janeiro, at the 2016 Games, "We are going to be one of the 'it' sports -- people are going to be watching, asking, 'Let's see why this sport deserves to be in the Olympic Games.' People are going to be paying attention.

"I think," he said, "we have all the tools."