MONACO — Transparency. What a concept.

The reform plan put forward by International Assn. of Athletics Federation president Seb Coe, so overdue, is full of common sense. It’s just the thing to start moving track and field, in particular its long-convoluted governance structure, ahead in the 21st century. "Transparency sits at the heart of everything we've been talking about," Coe would say late Saturday.

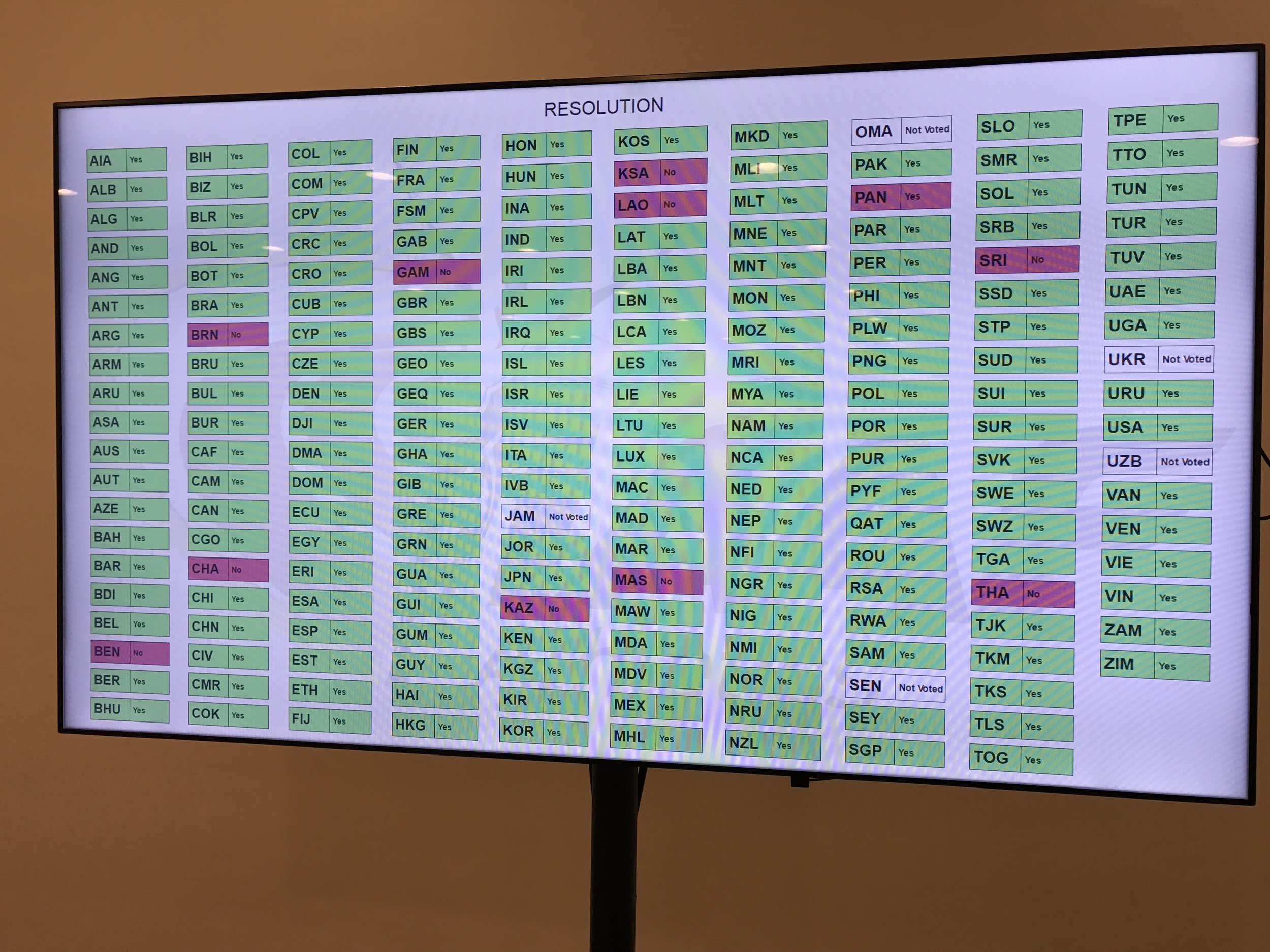

Like, for instance, an open vote. In which every yes, no and abstention was not just tallied but shown up on the big screen Saturday at a special IAAF congress held here in a ballroom at the seaside Fairmont Hotel.

Take note, International Olympic Committee and others. Transparency surely changes the way you approach the whole voting thing.

Thanks to an open vote and Coe's political skills, the IAAF reform package passed, 182-10, a "ringing endorsement of our commitment to do things differently," he said afterward but one that now -- given the backstage drama that attended the run-up to the balloting and, despite the landslide, remains very much a vital part of the IAAF scene -- raises the pressing question of real-life implementation.

Coe now has authority and real room to maneuver. But don't anyone be fooled that it will all be roses and sunshine.

The former IAAF president, Lamine Diack? From Senegal. Senegal, as was made plain because the ballots were transparently on display, abstained in Saturday's voting.

The runner-up in the 2015 election that made Coe president, Sergei Bubka? From Ukraine. Ukraine abstained.

"We made a decision today but it will be very important to fulfill that with real life," German delegate Dagmar Freitag observed after the vote. "Work begins today."

It actually began months ago, after last Christmas, and culminated late Friday, amid the IAAF awards ceremony, where word was the reform package’s fate remained highly uncertain.

Why is easy to explain:

Big-picture reform? Check. The sport's future on the line? Check. But what about the import of reform on matters such as personal agendas, perks of membership and, of course, individual advancement?

Translation, and cutting right to the core of the thing: what’s in it for me?

This of course is what drives critics of international sport — where considerable lip service is paid to the notion of athletes at the core of the enterprise — up the wall.

Maybe rightly so.

But it also is what it is, and to ignore that reality is unquestionably naïve.

Naïveté is not a helpful thing in the context of IAAF politics and culture. Particularly in 2016.

Track and field arrived at Saturdays moment after a grim 16 months. That's how long Coe has been president.

It was always clear that Diack, president from 1999 until 2015, ran the IAAF as his personal fiefdom — a model he learned from the president before him, Italy’s Primo Nebiolo.

What had been hidden, and for obvious reasons, according to accusations from the French authorities, is that Diack ran a closely held conspiracy — involving just a few senior officials — that aimed, among other things, to collect illicit payments in exchange for hiding certain Russian doping matters.

As for Russian doping — the IAAF banned the Russian track and field team from the 2016 Rio Games in the aftermath of allegations of state-sanctioned doping. A second report on the matter from Canadian law professor Richard McLaren report is due to be made public Friday.

If ever a sport and a situation were ripe for reform, this would seem to be the moment. Right?

As Usain Bolt said Friday, "I know Seb Coe is trying to make track and field more transparent so everyone can see what's happening, so one person is not pulling control. That's a bold move for him, a bold move for the IAAF president."

As Coe himself said in Saturday's opening remarks, “The walls of the organization were too high to see over and too much power rested in the hands of too few people,” adding, “We should have known more.”

He asserted, “We can not let this happen again,” adding, “It’s bad enough that any of this happened. But it can not happen for a second time. Not on our watch or anyone else’s watch."

In general, the IAAF proposal sketches out four areas of focus:

1. Independent anti-doping, integrity and disciplinary functions, the idea to launch an integrity unit in April 2017

2. A better gender balance

3. A bigger voice for athletes

4. A redefinition of roles and responsibilities for each national federation with the concurrent idea of strengthening what in IAAF terms is called “area representation,” broadly speaking the continents.

The proposal further suggested that IAAF business decisions be delegated to an executive board that would meet regularly, roughly once a month. The IAAF council would set policy. The congress, with a registry of more than 200 national representatives, would continue to be the federation’s “supreme authority,”meeting annually.

The idea, per the working paper, was to cast one vote Saturday on the adoption of two — count them, two — constitutions. One set of rules would take effect in 2017, the other in 2019. The 2017 plan revolved mostly around the integrity plank. The rest — a new structure for vice presidents, council and executive board — would take effect in 2019.

As Coe put it in the forward to the working paper, “Now is the time for change. The time to rebuild our organization for the next generation. To be the change we want to see.”

Svein Arne Hansen, president of the European Athletics Federations, wrote in a statement posted to the federation’s website: “To be clear, our sport’s reputation has already been damaged and failure to pass these reforms will do further damage in the eyes of the public, with governments and with partners in ways we can only imagine at this time. It will hurt the federations and it will hurt the athletes at all levels.”

That elicited on Twitter this response from Paula Radcliffe, the British marathon standout:

https://twitter.com/paulajradcliffe/status/804734851635093504

In remarks that helped to open Saturday’s session, Haile Gebrselassie, the distance champion who is now head of the Ethiopian track and field federation, said, “Billions of people around the world, they have to trust us.”

Echoed Andreas Thorkildsen, the Norwegian javelin champion: “It’s transparency and trust — what I believe is very important for us going forward.”

A few moments before, Prince Albert of Monaco had told the audience, “Today is a pivotal moment for the future of athletics,” meaning track and field, “and the hopes and dreams of clean athletes worldwide.”

The prince added, “Sport has the unique capacity to transcend borders, to build bridges between populations, to ease tensions within societies. We all need to make sure it remains a force for good a beacon of hope for generations to come. We need to rebuild this trust.”

All this uplifting stuff. All this excellent theater. All good.

Now let’s talk straight.

“Today is the day we must bury our own interests for the greater good — to do what is right,” the chair of the IAAF athletes’ commission, Rozle Prezelj of Slovenia, said.

As always, the devil lurks in the details, and in the difference between theory and practice.

Coe acknowledged from the head table that he had gotten pushback before the meeting about bringing in new people and new teams, including chief executive Olivier Gers. Referring to the clear concern underpinning that pushback, was it because “I want to ditch responsibility?”

He answered the rhetorical question: “Simply not true. Given the year that our sport and I personally have gone through, I hope all of you in this room will agree that is ridiculous,” even though obviously some in the room had been the ones making that “ridiculous’ suggestion and such pushback revealed the concern if not fear of moving from president-as-king governance structure that had long held at the IAAF.

That gender balance thing:

The IOC has for years pushed those in the Olympic movement to not just promote but welcome women at executive and leadership positions.

Progress has been halting.

The IAAF proposal perfectly illustrates why.

It calls for the number of vice presidents to stay at four with the proviso that by 2019 there be one of each gender and by 2027 two of each.

Let’s say you were one of the four men currently holding a vice-presidential seat. How inclined would you be to robustly agree to such a proposition if such agreement put you at serious risk of losing your position?

And what about section 3.6 in the proposals, relating once more to those vice presidents. It says a vice president can’t simultaneously serve as an area president.

Such “interlocking directorates” have long been a mainstay of Olympic sport despite the potential for conflict of interest, the rationale behind 3.6. It’s nonetheless easy to see why, in real life, such a change would mean a significant diminishment of authority and influence for someone who might currently occupy both spots.

As for the image of the sport and the ability to instill trust:

In theory, very few dispute the notion that stuff failing the smell test shouldn’t happen.

In practice, however, what smells in one part of the world maybe doesn’t in another.

For instance, explain this, and it’s not like it’s a secret, because anyone can read all about it right there on the internet:

The Assn. of Balkan Athletics Federations is a thing. It has 17 members. From, mostly, the Balkans — you know, the likes of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro.

So why was the “6th Balkan Athletics Gala,” according to the internet, held Nov. 19 in that bastion of Balkan-ness, Dubai?

Where the presidents and general secretaries of those member federations were invited to “share the excitement of the glorious moments”?

Hypothetically: what if a key player in Dubai had regional if not global ambitions? Would such a person stand to gain influence with some number of potential voters by inviting them out of the chill of the autumnal Balkans down to sunny Dubai?

Oh, the currents -- and thus the genuine concern from many of the reform-minded on Friday night.

The IAAF, meanwhile, made life all the more difficult for itself Saturday by insisting on what per the rules was called a “special majority” to enact its reforms — in essence, a two-thirds majority.

In all, 197 delegates (up from an initial count of 196) were on hand. Two-thirds meant 132 (if no abstentions).

A test question highlighted the obstacles: are you happy to be in Monaco? 177 said yes, 17 no, a couple had no opinion. Seventeen people were not happy to be on an expenses-paid trip to one of the world’s fanciest destinations? A second run-through of the test question, after the number of delegates was fixed at 197, gave these results: 156-37, 81 percent to 19 percent, with four abstentions.

Later, the Portuguese representative observed that such transparency was highly unusual at a sports function, and that many delegates had taken a cellphone picture of the results up there on that big screen. Would the real votes be displayed as well?

Yes, Gers said.

“For those who don’t want the vote to be transparent: make the right choice,” Radcliffe said from the floor, her hands quivering with emotion as she clutched the microphone.

In the end, that very transparency unquestionably helped seal the deal. No question by Saturday morning the Coe political operation meant the package would have passed the two-thirds threshold. But, also unquestionably, there would have been considerably more no votes. It’s another for everyone in the “family” — as that word was used many times in the 42 pre-vote floor comments — to talk the talk. It's quite another to see a very public “no” vote on a matter of such import.

No votes came from, among others, Saudi Arabia and Thailand.

Immediately after, Bobby McFerrin came on the audio feed: “Don’t worry. Be happy.”

Another choice might well have been Johnny Nash's 1972 No. 1 hit -- or if you prefer, the 1993 Jimmy Cliff version on the soundtrack of the Jamaican bobsled flick Cool Runnings. It famously proclaims, "I can see clearly now."

Next votes. Because there are plenty yet to come.

"Look," Coe said in a post-vote news conference, "I hope the public perception of our sport is helped by what they’ve seen today but that isn’t primarily why we did it. We did it because we were in need of change."