The Olympics can and should be a wonderful thing. Further, the International Olympic Committee naturally wants to be viewed in a positive light for the Games and for the many good things it does each and every day around our world. But increasingly the Olympic movement generates — day after day, week after week, year after year — negative headlines. Why?

Corruption allegations tied to recent editions of the Games (Rio, Sochi). Government-underwritten cost overruns tied to recent editions of the Games (Rio, Sochi, London, Beijing, Athens). Stadiums and sports venues abandoned to rot in the sun (Rio, Athens). And more, way more. What kind of business model is that?

“Celebrate Olympic Games,” the IOC says. Right now, taxpayers — and particularly in western Europe, the Olympic movement’s longtime base — seem more apt than not to say, are you kidding?

This is of the IOC's doing.

The time has come to break this cycle. Like, now.

Any individual or entity in the public space can expect some measure of negative press. But the drumbeat now is relentlessly, almost uniformly, negative; social media amplifies the negativity; the negativity brings with it an associated risk; that risk cuts to the core, indeed the soul, of the Olympic enterprise.

The movement has arrived at one of those moments where it must confront reality. Wishes and sentiment can be lovely. But not now. It's reality time.

IOC leadership and the members, both, must recognize and acknowledge, both, that they have to wean themselves off government money.

At least for this current bidding cycle, meaning for the 2024 Games.

Because it’s government money that has them in this predicament.

Going to Los Angeles for 2024, a privately funded bid and (if it wins) organizing committee, will buy the IOC needed time and stability. The other 2024 option is Paris, a continuation of the very thing that has gotten the IOC in this jam, a government-underwritten bid and (if it wins) organizing committee.

Stability will buy time. With that, the IOC can (and should) engage some of the world's most creative minds to apply needed innovation to the next Winter and Summer Games bid rounds.

Stability in particular means the construction of no permanent venues. It means a focus on what the Olympics should be about -- sports, not soil remediation or sewer pipes or light-rail lines.

Stability will also, and this is just common sense, ease one twist on the bad press: seven years of pre-Games sky-is-falling headlines.

Consider what's happening in Japan with Tokyo 2020: a steady spotlight on finances, construction and bricks-and-mortar legacy issues. Back to the run-up before Rio: recall Zika, pollution, security, construction and more.

None of that is remotely "celebration."

Here’s a really easy segue:

The central concept animating far too much of the process now is trusting politicians. That's funny. Because who trusts politicians? The IOC, apparently. Anyone else?!

A short recap (could be a lot, long longer) about trusting politicians with a short (also could be a lot longer) note about what the next few weeks might have in store:

— Days after the Rio Games ended, Rio Mayor Eduaro Paes was awarded the IOC’s highest honor, the “Olympic Order.” Now he is being investigated for allegedly accepting $5 million in bribes tied to Games-related construction projects. His spokeswoman called the accusations “absurd and untruthful.”

— The former governor of the state of Rio, Sergio Cabral, who helped win the Games in 2009, was arrested last November with authorities saying he led an organized crime ring that diverted roughly $64 million in bribes for the renovation of Maracanā Stadium and two other projects.

The stadium staged the 2014 soccer World Cup final as well as the 2016 Olympic opening and closing ceremony. Photos of its decay post-closing ceremony have flashed around the world.

— Federal prosecutors filed corruption charges last September and again in December against Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the former Brazilian president who played a key role in Rio’s winning 2009 bid. The charges were not Olympic related. Authorities allege that Mr. da Silva oversaw a far-reaching system of kickbacks and more.

— Mr. da Silva’s successor, Dilma Rousseff, was in limbo during the Games, her powers and duties suspended May 12 for six months. On August 31, 10 days after that closing ceremony, she was removed from office.

- Reports last week tied Ms. Rousseff’s successor, the current Brazilian president, Michael Temer, to a deal involving a $40 million bribe. Mr. Temer, in an emailed statement to the Wall Street Journal, called the allegation an “absolute lie.”

— Switching to South Korea, site of the next Games, the Winter Olympics next February:

The National Assembly voted in December to impeach the president, Park Geun Hye. Last month, a ruling by the country’s Constitutional Court formally ousted her, determining that she not only had conspired with a confidante to extort money but had tried to conceal her misconduct.

-- Switching to Japan:

Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike's two immediate predecessors — Naoki Inose and Yoichi Masuzoe — resigned over funds-related scandals, both since Tokyo won in 2013. The Tokyo bid book said costs would, all-in, total $7.8 billion. Working figures now are in the $15 billion range -- this months after a government panel warned it could be $30 billion.

— Switching to France, with an eye toward the coming weeks:

The country’s two-stage presidential election is coming up. Most believe Marine le Pen will win the first round. After that, who knows?

Whether she prevails in Round Two or no, this thought:

Last month, Le Monde reported that a company with ties to the IOC member Frankie Fredericks of Namibia received a roughly $300,000 payment from a business owned by Papa Massata Diack, the former marketing director for the IAAF, track and field’s worldwide governing body, on the day the IOC selected Rio for 2016.

Fredericks had been chairing the IOC 2024 “evaluation commission.” He stepped down and has been replaced by Patrick Baumann of Switzerland. The commission is due to tour LA and Paris next month.

The former IAAF president Lamine Diack is currently under arrest in France as authorities investigate money laundering and bribery accusations tied to allegations he helped cover up positive Russian drug tests. Papa Massata Diack, his son, is wanted by Interpol on bribery and Interpol accusations.

It is believed the French authorities by now know more about considerably more IOC and IAAF members. Whether what they know becomes public — particularly after the rounds of the French elections — remains a matter of keen speculation. One school of thought: left-leaning French judges would have more reason to leak to Le Monde or elsewhere after the Socialists, if predicted, get humbled in the French presidential elections? Stay tuned.

Now, after that recap, to close the circle:

The Olympic world has, for years, tied itself to public-sector spending. In years past, there may have been a sound argument to be advanced for such spending. A project the size and scope of an Olympic Games is about mitigating risk, and having what amounts to an unlimited government bank account may seem like a sure way to mitigate risk.

The past few years have proven that's not true.

Public-sector spending is still incredibly risky.

Why?

Because you are completely dependent on politics.

That is, you are putting your faith in the political dynamic.

And that dynamic is shifting. Every which way. Any which way.

A project that might be important to one political party — say, an athletes’ village, which Paris has to build, at a cost already projected over $1 billion — might, or might not, be so important to the next. That is a considerable, and unforeseeable, risk.

Further:

In our social media age, perception is as important as reality. The IOC president, Thomas Bach, said exactly this, at the SportAccord conference two weeks ago in Denmark, in a different context, the anti-doping sphere. Even so, his words resonate:

"In a world where the integrity and credibility of sport is scrutinized by a skeptical public like never before, perception sometimes and even more often becomes reality."

When projects go sour, when you’re talking about corruption, money has to come from somewhere. In a developing country such as Brazil, the optics are made all the worse. If the argument is, OK, but Japan is not a developing nation (neither is France), so why use Brazil? Answer: because the images from Brazil are the ones freshest in the public mind, and when the members vote for 2024 at the IOC assembly on September 13 (assuming there is a vote -- that is, no 2024/2028 deal), it will be those Rio images that will be the easiest, most convenient and, let's be honest, most provocative from which to draw.

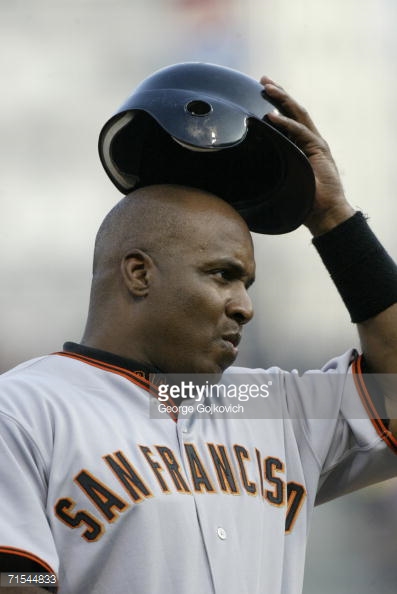

Remember this airport banner last year in Rio?

Again, public money has to come from somewhere. Is it coming from the police, the firefighters, the schools, hospitals or some other institution that provides for the public welfare?

This, in a nutshell, is why the Olympic movement is so uniquely vulnerable — to proof or even allegation of public corruption.

Social media -- which zaps images, memes and provocations across the world in an instant -- ramps up the intensity attached to that vulnerability. The IOC is as establishment as it gets. It tends to be traditional, conservative and cautious. It apparently has developed no articulated strategies -- none -- to deal with the fast pace of aggressive, unapologetic social media and to confront this vulnerability. As a sign of how like a battleship (takes a long time to turn) the IOC moves: it took two years to hire a new director of strategic communications, a move announced within the past few days.

The IOC needs stability. It needs time.

Even 10 years ago, this vulnerability and these sorts of risks confronting the IOC weren't anywhere near the same.

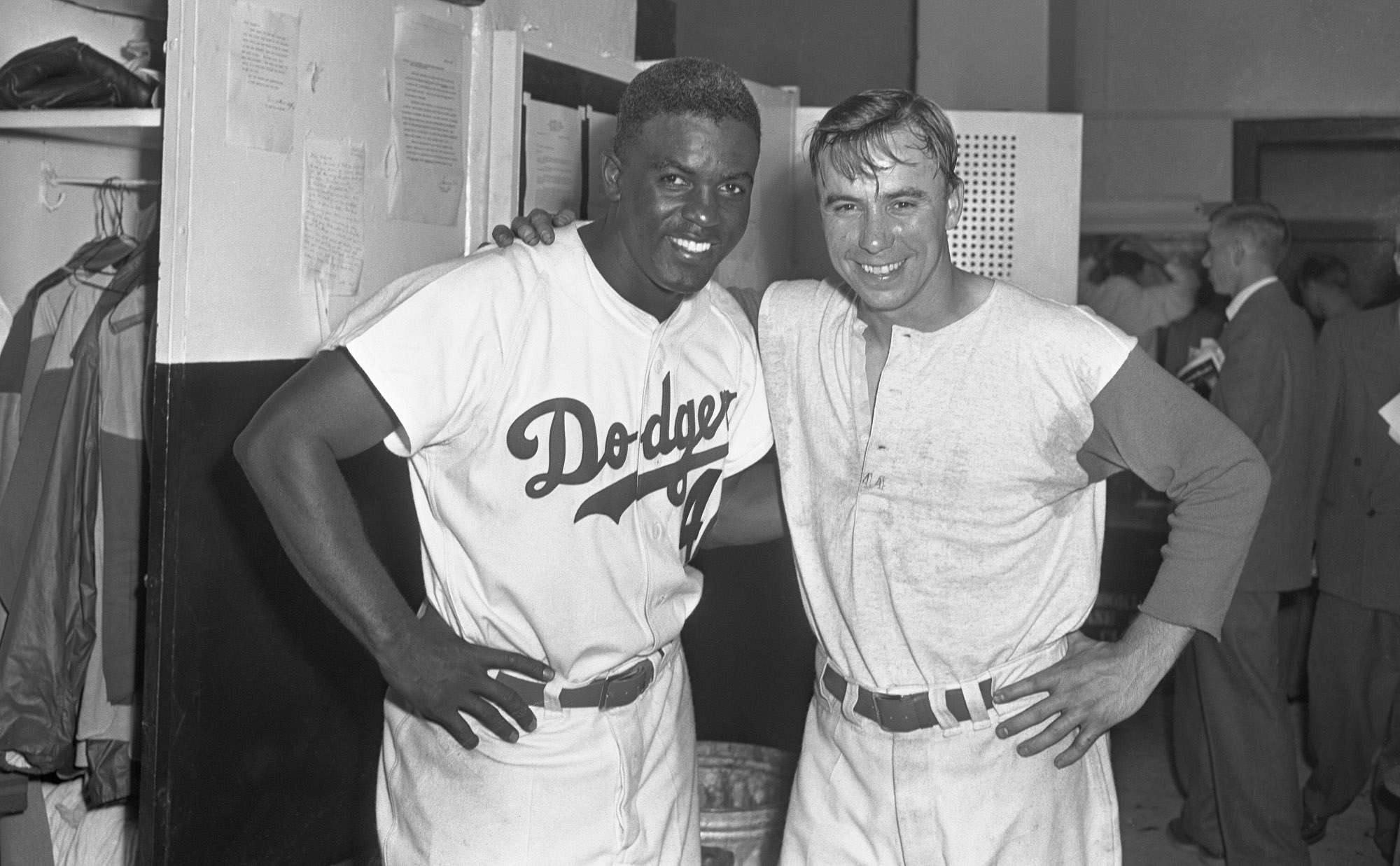

That summer, 2007, the members elected Sochi for 2014.

Sochi led to a reported $51 billion bill.

That $51 billion bill got the IOC where it is now -- along with $40 billion for Beijing, $20 billion (who knows, really) for Rio, $15 billion for London, $11 to 15 billion for Athens and on and on.

Of course it's not risky, financially, for the IOC to go to totalitarian/authoritarian countries. That’s the situation it confronted two years ago in the race for the 2022 Winter Games, when it could attract only China and Kazakhstan, Beijing (no snow in the mountains) winning, 44-40.

Going to totalitarian/authoritarian countries entails an entirely different category of risk.

One is manifestly plain: the IOC can’t go, one Games after another, to totalitarian/authoritarian countries.

And taxpayers in western democracies have had enough of corruption and cost overruns.

The solution is obvious.