The International Olympic Committee, like the Kremlin, speaks in code.

Let us now decode Friday’s announcement from a meeting in South Korea of the IOC's policy-making executive board that a “working group” made up of the four IOC vice-presidents has been set up to "explore changes" in Olympic bidding. The obvious subtext: the possibility later this year of jointly awarding the 2024 and 2028 Games to Los Angeles and Paris or, you know, Paris and Los Angeles.

This panel is due to make its report at what is called, in IOC jargon, the “technical briefing” in mid-July in Lausanne, Switzerland, the show at which those two candidate cities get to make presentations before the big event itself, the September 13 vote — if there is going to be a vote — in Lima, Peru.

The announcement Friday comes as IOC confronts almost everywhere it looks what in gentle terms would be called a credibility gap. The IOC stands as the symbol of an establishment that regular people increasingly resent, and a lot. These regular folks, who in western democracies are taxpayers, have made it plain that they will accept the IOC only on certain terms.

Meaning their — taxpayer — terms. Which means back to the future. Which means 1984.

In this volatile and perhaps even existential moment for the Olympic movement, you know the sort of thing that further erodes IOC credibility, and in a big way?

When the 73-year-old Swiss head of the international ski federation, Gian-Franco Kasper, opens up his mouth and, like he did at that very same IOC meeting in Korea, draws an analogy to allegations of Russian doping: "I'm just against bans or sanctioning of innocent people. Like Mr. Hitler did — all Jews were to be killed, independently of what they did or did not do.”

He also reportedly said, "We call this sippenhaft in Germany — where the place you come from makes you guilty.”

The place Mr. Kasper is from is a canton in Switzerland where sits St. Moritz, site of the 1928 and 1948 Winter Games. There, twice in the past four years voters have been asked via the ballot whether they would be interested in staging the 2022 or 2026 Winter Games. Twice the answer, most recently during the 2017 alpine ski championships: no.

Mr. Kasper’s words were so offensive and ill-timed, given everything at stake, that the IOC itself issued an apology on his behalf.

It is with this sort of ever-shifting and complex backdrop in mind that one approaches a more subtle decode of IOC "working group" messaging.

No. 1:

Whatever the IOC president wants is what the “working group” will “present” in July.

This is the way the IOC works. Now, then, presumably always.

If you don’t understand this basic premise about the IOC, you are still charmingly enrolled in naive school, which is fine but not the way the Olympic sphere operates.

The current IOC president, Thomas Bach of Germany, learned this from Juan Antonio Samaranch of Spain, president from 1980-2001. Outsiders hold to a stereotyped perception of Mr. Samaranch. The long view of history is more likely to trend toward a keen appreciation of Mr. Samaranch's style and manner of global leadership.

No. 2:

The four vice-presidents do not come to the table as neutrals.

Australia’s John Coates has every reason to push a Brisbane bid for 2028. Turkey’s Ugur Erdener, same for Istanbul. Spain’s Juan Antonio Samaranch Jr., absolutely for Madrid.

Then there is China’s Zaiqing Yu, and after Beijing for 2008 and 2022, why not Nanjing (Summer Youth Games 2014) or Shenzhen (Summer University Games 2011) or Shanghai for 2028?

Coates, Erdener and Yu are already on record as publicly opposed to the idea of a 2024-2028 double-double.

(Advice, IOC: you want the youth audience? Bring the Games back to SoCal sooner than later and send everyone to In-N-Out for the No. 1 special: double-double, fries, drink. Also, In-N-Out is a chain that encourages young people to, you know, read — a free burger for every five books that kids check out from the library and read. But I digress.)

Others who have said an Olympic double, hold the fries, may not make the best option: Gerhard Heiberg of Norway, the former IOC marketing director, and C.K. Wu of Taiwan, another executive board member and the boxing federation president.

That such heavyweights do not come as neutrals? Does not matter.

Why? See No. 1.

Moving on to No. 3:

With the announcement of this “working group,” the executive board bought itself roughly four months for Bach to canvass the Olympic scene’s wide range of stakeholders on the notion of a 2024-2028 double.

In this case, canvass is again code. It means, from the IOC president’s position, sure, I am glad to listen to you. Done? OK, now my turn, and be sure to listen closely, please, because we are facing some issues and we need to find a solution.

Mr. Bach, meanwhile, is walking a tremendous high-wire act, which he and perhaps only a few confidantes truly understand.

— Starting with the IOC members themselves:

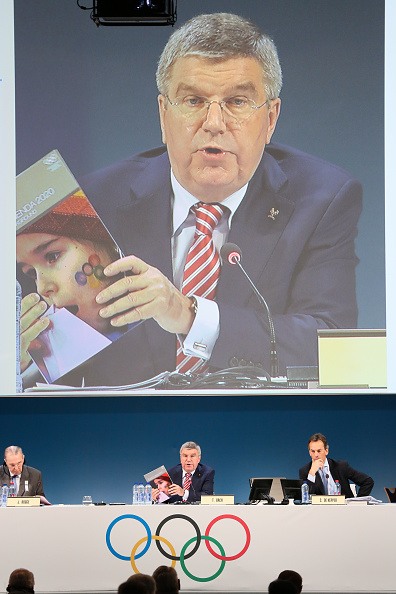

In December 2014, Mr. Bach pushed through the IOC membership a purported wide-ranging reform plan dubbed Agenda 2020.

As evidence that the IOC does what the president wants: Agenda 2020 (all 40 points) was approved unanimously.

The reforms have so far failed to convince taxpayers in any number of European cities that they are in the least bit meaningful, leaving only two candidates in the 2015 vote for 2022 (Beijing and Almaty, Kazakhstan) and, now, for 2024 (LA, Paris).

A good many of the members already complain, if not for attribution, that being a member might make for a great way to speed through passport lines but what else? Being an IOC member is entirely a volunteer position. It carries no defined mandate. A member’s key “job” has in many ways been reduced to voting in the candidate city elections. And now, for 2024 and 2028, the IOC president would take that away?

Even more, for the 2022 Games race just two years ago, the situation was exactly the same — two cities — and yet the members duly exercised their franchise?

What’s so different now?

— Sticking with Agenda 2020:

In discussion about a 2024-2028 double, this space has made plain that the only way such a twist would work is that if it were LA for 2024, Paris for 2028.

Some European friends have floated the idea of Paris first, LA for 2028.

Our Paris bid friends suggest that it would have to be Paris first in any such rotation because the tender for the land on which an athletes’ village would have to be built is only available for 2024.

If past history is a reliable guide, and it is, the village would indisputably sink into a fat and ugly construction cost-overrun and delay-plagued boondoggle.

To reiterate, that is the very last thing the IOC — and beyond, the broader Olympic movement — wants or needs.

What all involved want and need is time and stability.

At any rate, if that tender is the sticking point, French friends: if it’s that critical to your project, get a better lawyer. That is just common sense. Maybe, you know, find a way to figure out how to make it happen instead of saying, all French-like, non, we cannot.

— Back to the IOC president and Agenda 2020:

Mr. Bach was elected to a first eight-year term in 2013.

Let’s say for purposes of discussion that the IOC’s fascinatingly insightful new friends in the French prosecutor’s office, having already reached out to Frankie Fredericks, the IOC member from the west African nation of Namibia, don’t so intrude on Mr. Bach’s fate that he can fulfill not only that eight-year term but can, indeed, serve — as is IOC custom since the reforms associated with the late 1990s Salt Lake City affair — a second four-year term as president.

Math: the year 2013 plus 12 would take us to the year 2025.

Common sense:

Agenda 2020 is Mr. Bach’s project.

He is hugely invested in, indeed professionally identified with, making it real.

Assuming 12 years in office, the only Summer Games on Mr. Bach’s watch during which Agenda 2020 could be seen through, start to finish, would be 2024.

Of the two bids, the only Summer Games that even remotely aligns properly with Agenda 2020 is Los Angeles.

The Paris people may well protest.

They say that 95 percent of their stuff is already built, and good for them.

It’s the items to be built that are the killers — that athletes' village, an aquatics center and media housing. Those are big-ticket projects, and big-ticket items are at the core of what is killing the IOC’s credibility with taxpayers, because these projects are marketed as cost-factor x but then inevitably become real-cost x-plus. (Tokyo 2020: 2013 bid book $7.8 billion; post-2013 win as high as $30 billion; maybe now $15.2 billion, according to Bach. See, French friends? If the Japanese can cut $15 billion, you can find a good lawyer!)

The IOC president would never, ever — repeat, never, ever — say in public that big-ticket items like these are, in fact, killers.

Sports politics is absolutely politics, and you do not get to be the IOC president without being an adept politician of the first order.

But, and he knows this, the IOC absolutely needs to get out of the government-backed project business. That’s not what the Games are about.

It perhaps may have been little noticed except within certain Olympic precincts but last week offered up 110 percent evidence to that exact point: why the IOC desperately needs to get out of the business, at least for a safe-harbor seven-year stretch, of having sports events essentially backed — as Paris is and Los Angeles is not — by government.

There's something of an irony here: the IOC held its 2011 assembly in Durban, South Africa, and it was there that the IOC elected Pyeongchang, South Korea, the site of the 2018 Winter Games, which was where the IOC announced Friday it was going to have this "working group" all about 2024 and 2028.

Earlier in the week, Durban backed out of hosting the 2022 Commonwealth Games, the president of the South African Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee saying that “without the necessary government guarantees, we couldn't move on.”

This comes of course just a few weeks after Budapest dropped out of the 2024 Summer Games campaign — following earlier exits by Rome and Hamburg, Germany.

It’s just so obvious what is what.

As in 1984, the LA 2024 project would be privately financed.

Decoding, again:

That’s what these next four months, and the behind-the-scenes talks, will be about while the "working group" does its thing.

If ever you wanted proof of how the IOC itself is struggling mightily in 2017 to bridge that credibility gap, consider:

At that meeting in Korea, the Games’ executive director, Christophe Dubi told a small pack of reporters that the Summer Games last year had “changed the sewer system” in Rio de Janeiro.

First and foremost, an Olympics is not now, was not then, will not ever be about changes to a city’s sewer system.

To appropriate one of Mr. Bach’s pet phrases, that is not what gets 16-year-old would-be surfing and skateboarding couch potatoes off the couch.

Secondly, with all due respect for Mr. Dubi, who is a fundamentally decent guy whose position often puts him between a rock and a sewage outlet, so to speak, that assertion simply cannot be true.

Each and every day in Rio, on the way into the Main Press Center, thousands of us were welcomed by the delightfully fragrant, indeed welcoming bouquet of an open sewage trench.

Decode: let’s cut the crap, people.

For 2024, Los Angeles. That buys time and stability, and access to the key youth demographic and the buzz and tech of California, and all those things are critically what's at issue, as well as perhaps the chance for Mr. Bach to see his reforms put into action while he’s IOC president. If Paris wants 2028, that’s altogether another matter. Some good lawyers can work that out.